REMBRANDT HARMENSZ VAN RIJN

1606 Leiden - Amsterdam 1669

Click images to toggle info

-

![]()

The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight 1654

etching and drypoint; sheet 213 x 163 mm (8 3/8 x 6 7/16 inches)

Bartsch 83, White/Boon only state; Hind 280; The New Hollstein 286 first state (of four)WATERMARK

foolscap with five-pointed collar (Hinterding variang G-b-a; vol. 2, p.123, vol. 3, p. 214 ill.)PROVENANCE

P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London (their stock no. in pencil verso C.31001 (1/2)

private collection, GermanyA fine impression with patches of burr in the central group of figures; in impeccable, untreated condition with small margins all around.

-

![REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN 1606 Leiden – Amsterdam 1669 The Triumph of Mordecai ca. 1641 etching and drypoint; 175 x 213 mm (6 3/4 by 8 1/2 inches) Bartsch 40, White/Boon only state; Hind 172; The New Hollstein 185 third state (of four) WATERMARK shield with Strasbourg bend (Hinterding, vol. 2, p. 182, variant A-a-a; vol. 3, p. 366 ill.) PROVENANCE Gilhofer & Ranschburg, Lucerne Carl and Rose Hirschler, née Dreyfus, Haarlem (Lugt 633a), acquired in May 1927; thence by descent]()

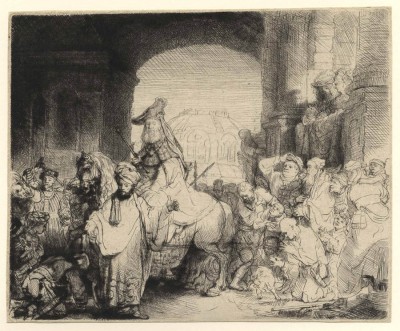

The Triumph of Mordecai ca. 1641

etching and drypoint; 175 x 213 mm (6 3/4 x 8 1/2 inches)

Bartsch 40, White/Boon only state; Hind 172; The New Hollstein 185 third state (of four)

WATERMARK

shield with Strasbourg bend (Hinterding, vol. 2, p. 182, variant A-a-a; vol. 3, p. 366 ill.)

PROVENANCE

Gilhofer & Ranschburg, Lucerne Carl and Rose Hirschler, née Dreyfus, Haarlem (Lugt 633a), acquired in May 1927; thence by descentA superb, very early impression with substantial burr in the drypoint work, particularly toward the left, but also printing strongly and with touches of burr at right and therefore allowing for a very balanced composition. The sheet is in impeccable, untreated condition with thread margins all round.

Hinterding and Rutgers, the authors of The New Hollstein on Rembrandt, discovered three impressions pulled when small details on the plate had not been finished; they describe them as a unique first state and as a second state that is known in two impressions. Their fourth state is a very late, eighteenth-century reworking of the original plate.

The Triumph of Mordecai shows a scene from the Old Testament Book of Esther in which the two main characters in a very complex story—Mordecai shown royally clothed and mounted on a horse, and Haman, his enemy, forced to act as his herald, standing in the foreground—are as yet unaware of their imminent fates. For King Ahasuerus has been informed by Esther, his Jewish consort, of the dastardly plot hatched by Haman, his favorite: since Mordecai, Esther’s stepfather, has refused to pay him homage, Haman intends to massacre all the Jews in the empire and to hang Mordecai from a gallows that he has already had erected. In the meantime, the king has discovered that Mordecai has foiled an attempt on his life and thus honors him with this procession. Mordecai is not yet aware of the reason for his royal treatment and Haman does not realize that he is the one who will, in fact, be hanged on the gallows.

In his etching Rembrandt referred to two other depictions of this scene: Lucas van Leyden’s engraving of 1515 (Bartsch 32), an almost frieze-like composition populated by a large crowd paying homage to Mordecai, and a painting of 1621 by Rembrandt’s teacher Pieter Lastman in which the scene is given more emotional and perspectival depth. If Rembrandt incorporated elements of both of these works into his version, in execution it represents a bravura display of a range of printmaking techniques that is entirely characteristic of his work.

-

![REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN 1606 Leiden – Amsterdam 1669 The Great Jewish Bride - Saskia 1635 etching, engraving, and drypoint; 223 x 167 mm (8 3/4 x 6 9/16 inches) Bartsch 340, White/Boon fifth (final) state; Hind 127; The New Hollstein 154 fifth (final) stateWATERMARK Strasbourg bend (Hinterding, vol. 2, p. 182–184, variant A, vol. 3, pp. 366–368 ill.) PROVENANCE Ernst, Prince of Saxe-Meiningen (1859–1941; with the Colnaghi director Harold Wright’s pencil annotation on the verso S.43801) P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London (their stock nos. in pencil verso C.16303 and C.28044) A fine, rich impression; in excellent condition with thread margins, in a few places trimmed on the plate-mark. The female sitter is depicted with free-falling hair under a string of pearls, a coiffure worn by Jewish maidens in seventeenth-century Holland when they were betrothed. Furthermore, the sitter holds prominently a roll, most likely the Ketubah. However, Madlyn Kahr’s suggestion (“Rembrandt’s Esther: A Painting and an Etching newly interpreted and dated”, in: Oud Holland, vol. 81 (1966), pp. 228 ff.) that the print represents Queen Esther preparing to meet King Ahasuerus to beg the lives of the Jewish people in Persia seems also plausible explanation of the subject matter. Despite the elaborate dress-up and the print’s traditional title, this image can be counted among Rembrandt’s most directly descriptive portraits of his first wife, Saskia Uylenburgh (1612–1642) whom he had married the previous year. Her features are clearly recognizable. Rembrandt recorded her pose in this historical costume in a fairly detailed preparatory drawing in reverse that is now in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (Benesch 292) on which the print is based.]()

The Great Jewish Bride - Saskia 1635

etching, engraving, and drypoint; 223 x 167 mm (8 3/4 x 6 9/16 inches)

Bartsch 340, White/Boon fifth (final) state; Hind 127; The New Hollstein 154 fifth (final) stateWATERMARK

Strasbourg bend (Hinterding, vol. 2, p. 182–184, variant A, vol. 3, pp. 366–368 ill.)PROVENANCE

Ernst, Prince of Saxe-Meiningen (1859–1941; with the Colnaghi director Harold Wright’s pencil annotation on the verso S.43801)

P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London (their stock nos. in pencil verso C.16303 and C.28044)A fine, rich impression; in excellent condition with thread margins, in a few places trimmed on the plate-mark.

The female sitter is depicted with free-falling hair under a string of pearls, a coiffure worn by Jewish maidens in seventeenth-century Holland when they were betrothed. Furthermore, the sitter holds prominently a roll, most likely the Ketubah. However,

Madlyn Kahr’s suggestion (“Rembrandt’s Esther: A Painting and an Etching newly interpreted and dated”, in: Oud Holland, vol. 81 (1966), pp. 228 ff.) that the print represents Queen Esther preparing to meet King Ahasuerus to beg the lives of the Jewish people in Persia seems also plausible explanation of the subject matter.Despite the elaborate dress-up and the print’s traditional title, this image can be counted among Rembrandt’s most directly descriptive portraits of his first wife, Saskia Uylenburgh (1612–1642) whom he had married the previous year. Her features are clearly recognizable. Rembrandt recorded her pose in this historical costume in a fairly detailed preparatory drawing in reverse that is now in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (Benesch 292) on which the print is based.

-

![The Adoration of the Shepherds: With the Lamp]()

The Adoration of the Shepherds: With the Lamp ca. 1654

etching; sheet 110 x 134 mm (4 3/8 x 5 1/4 inches)

Bartsch 45, White/Boon second (final) state; New Hollstein 279 third (final) state

PROVENANCE

with C.G. Boerner (our stock number in pencil on verso zu 4853)

private collection, Germany (acquired in March 1961); thence by descentA posthumous but still very attractive and well-printed impression; the accidental, irregular gaps in the etched lines that distinguish impressions of the first state (and which Rembrandt himself did not attempt to correct) have now been filled in with fine cross-hatched burin lines; the sheet is in excellent condition and preserved with small margins all round.

This print is one of six etchings that show early childhood scenes from the life of Christ. They all date from around 1654 and are similar in their horizontal format and graphic style. Even in this scene, which, as the prominently featured oil lamp in the center of the composition indicates, is set in a dark interior, the linework is open and transparent. The six prints do not, however, form a proper “set” since they lack a concise narrative arc and have neither a beginning nor an end. The other scenes show Circumcision in the Stable (Bartsch 47), The Flight into Egypt: Crossing a Brook (Bartsch 55), The Virgin and Child with the Cat and Snake (Bartsch 63), Christ Disputing with the Doctors (Bartsch 64), and Christ Returning from the Temple with His Parents (Bartsch 60).

The “style of drawing and the proportion of the figures to the space they inhabit” is consistent throughout the series. All six prints display what Cliff Ackley describes as “the economical, suggestive shorthand combined with regular parallel shading that characterizes so many of Rembrandt’s etchings of the 1650s” (Cliff Ackley in Rembrandt’s Journey, exhibition catalogue, Boston/Chicago, 2003–04, p. 241). -

![etching, engraving, and drypoint; sheet 98 x 148 mm (3 7/8 x 5 7/8 inches) Bartsch 55, White/Boon only state; New Hollstein 277 only state provenance with C.G. Boerner (our stock number in pencil on verso zu 7059) private collection, Germany (acquired in March 1966); thence by descent]()

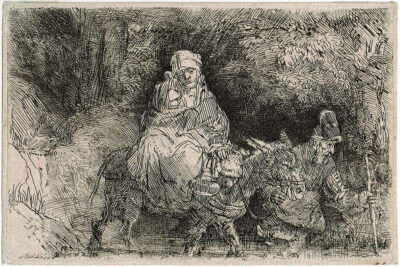

The Flight into Egypt: Crossing a Brook 1654

etching, engraving, and drypoint; sheet 98 x 148 mm (3 7/8 x 5 7/8 inches)

Bartsch 55, White/Boon only state; New Hollstein 277 only state

PROVENANCE

with C.G. Boerner (our stock number in pencil on verso zu 7059)

private collection, Germany (acquired in March 1966); thence by descentA good but later impression; in very good condition with small margins all round.

This print is part of the same group of etchings showing childhood scenes from the life of Christ that are described in the previous catalogue entry. It is Rembrandt’s last etched version of a subject he had previously treated in 1626, in one of his earliest experiments with the etching needle—The Flight into Egypt: A Sketch (Bartsch 54)—and to which he then repeatedly returned over a period of two decades, between 1633 and 1653 (Bartsch 52, 57, 58, 53, and 56, listed here in chronological order).

The plate for The Flight into Egypt: Crossing a Brook was not subjected to state changes, and the paper of our impression shows no watermark. We can therefore not say with absolute certainty when it was printed. However, while it still convincingly conveys the nighttime scene with its weary travelers, it clearly does not belong to those exceedingly rare early pulls, which are characterized by fine touches of drypoint burr and are often printed with subtle plate tone.