ROBERT NANTEUIL

1623 Reims - Paris 1678

Click images to toggle info

-

![]()

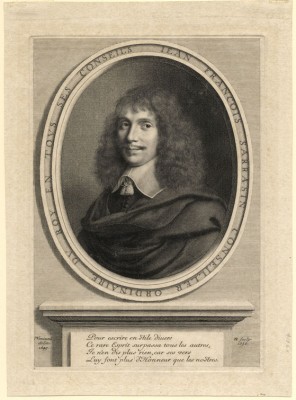

ROBERT NANTEUIL

1623 Reims – Paris 1678

Jean François Sarrazin 1656

engraving; 215 x 152 mm (8 7/16 x 5 15/16 inches)

Robert-Dumesnil 220; Petitjean/Wickert 203 first state (of five)PROVENANCE

Ducs d’Arenberg, Brussels and Nordkirchen, Westphalia (Lugt 567)It is unusual for Nanteuil to also give the date of the drawing. Here, he explicitly signs the print as delin[eavit] 1649 et sculp[sit] 1656.

-

![]()

ROBERT NANTEUIL

1623 Reims – Paris 1678

Hardouin de Péréfixe 1662

engraving; 328 x 257 mm (12 15/16 x 10 1/8 inches)

Robert-Dumesnil 211; Petitjean/Wickert 191 second state (of four)WATERMARK

oval ?PROVENANCE

Franz Baumgartner, Vienna (Lugt 975)

Rudolf Peltzer, Cologne (Lugt 2231);

his sale, H.G. Gutekunst, Stuttgart, May 2–8, 1913

Knoedler & Co., New York (their stock no. K 5596)

private collection, USA (acquired during the 1920s and 1930s)

by descent to the grandson of the collector

R.M. Light & Co. (acquired in the late 1980s) -

![]()

ROBERT NANTEUIL

1623 Reims – Paris 1678

Hardouin de Péréfixe 1663

engraving; 363 x 282 mm (14 1/4 x 11 1/8 inches)

Robert-Dumesnil 212; Petitjean/Wickert 192 second state (of three)WATERMARK

arms of Etienne de Meau (cf. Heawood 686)PROVENANCE

Max J. Bonn, London (Lugt 1878)

Knoedler & Co., New York (their stock no. K 2096 MK)

private collection, USA (acquired during the 1920s and 1930s)

by descent to the grandson of the collector

R.M. Light & Co. (acquired in the late 1980s)Hardouin de Beaumont de Péréfixe (1605–1671) was chamberlain of Cardinal Richelieu.